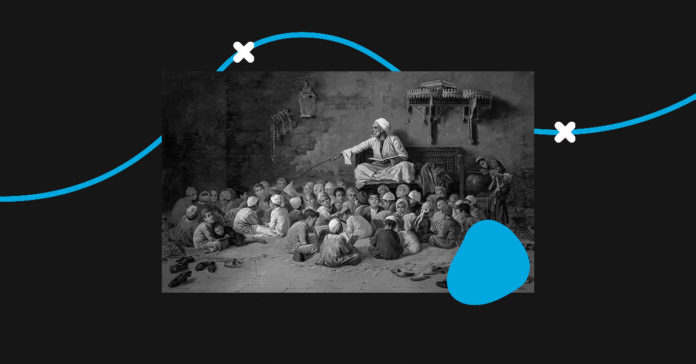

This comes about as follows. Severe punishment in the course of instruction does harm to the student, especially to little children, because it belongs among (the things that make for a) bad habit. Students, slaves, and servants who are brought up with injustice and (tyrannical) force are overcome by it. It makes them feel oppressed and causes them to lose their energy. It makes them lazy and induces them to lie and be insincere. That is, their outward behaviour differs from what they are thinking, because they are afraid that they will have to suffer tyrannical treatment (if they tell the truth). Thus, they are taught deceit and trickery. This becomes their custom and character. They lose the quality that goes with social and political organization and makes people human, namely, (the desire to) protect and defend themselves and their homes, and they become dependent on others. Indeed, their souls become too indolent to (attempt to) acquire the virtues and good character qualities. Thus, they fall short of their potentialities and do not reach the limit of their humanity. As a result, they revert to the stage of ‘the lowest of the low’.

That is what happened to every nation that fell under the yoke of tyranny and learned through it the meaning of injustice. One may check this by (observing) any person who is not in control of his own affairs and has no authority on his side to guarantee his (safety). One may look at the Jews and the bad character they have acquired, such that they are described in every region and period as having the quality of khurj,[1] which, according to well-known technical terminology, means ‘insincerity and trickery’. The reason is what we have said.

Thus, a teacher must not be too severe toward his pupil, nor a father toward his son, in educating them. In the book that Abu Muhammad b. Abi Zayd wrote on the laws governing teachers and pupils, he said: ‘If children must be beaten, their educator must not strike them more than three times.’ ‘Umar (RA) said: ‘Those who are not educated (disciplined) by the religious law are not educated by God.’ He spoke out of a desire to preserve the souls from the humiliation of disciplinary punishment and in the knowledge that the amount (of disciplinary punishment) that the religious law has stipulated is fully adequate to keep (a person) under control, because the (religious law) knows best what is good for him.

One of the best methods of education was suggested by Ar-Rashid to Khalaf b. Ahmar, the teacher of his son al-Amin. Khalaf b. Ahmar said: ‘Ar-Rashid told me to come and educate his son al-Amin, and he said to me: “O Ahmar, the Commander of the Faithful is entrusting his son to you, the life of his soul and the fruit of his heart. Take firm hold of him and make him obey you. Occupy in relation to him the place that the Commander of the Faithful has given you. Teach him to read the Qur’ân. Instruct him in history. Let him transmit poems and teach him the Sunnah of the Prophet (ﷺ). Give him insight into the proper occasions for speech and how to begin a (speech). Forbid him to laugh, save at times when it is proper. Accustom him to honour his relatives when they come to him, and to give the military leaders places of honour when they come to his salon. Let no hour pass in which you do not seize the opportunity to teach him something useful. But do so without vexing him, which would kill his mind. Do not always be too lenient with him, or he will get to like leisure and become used to it. As much as possible, correct him kindly and gently. If he does not want it that way, you must then use severity and harshness.”’

[Muqaddimah by Ibn Khaldun, p. 423-426]

Notes:

[1] This vocalization is indicated in B, C, and D. However, no such word in the meaning required seems to exist in Arabic dictionaries. Is it, perhaps, a dialect variant of Arabic khurq ‘charlatanry, foolishness’, or a Spanish or North-west African dialect expression?